Who Was Owen Brown?

A gravesite off of the El Prieto trail in Altadena provides a window into the inciting incidents preceding the US Civil War.

Los Angeles is a city of transplants. Despite the gridlock traffic, record-breaking heat waves, and outrageous cost of living, this little town in the desert continues to attract people from all over the world. Exposure to humans from all walks of life is one of the big draws of living here. Niche hobbies, obscure pastimes, and delicious culinary masterpieces — it’s the variety of experiences that make living in LA a vibrant and new experience every day.

I think Los Angeles lures people in because it’s a place where you can reinvent yourself and become whoever you want to become. Your place of origin doesn’t define you here, it’s where you’re headed that’s important. Do you want to be a movie star, a real-estate mogul, or the next TikTok influencer? Go for it. The possibilities are as endless as the traffic on the 405.

Despite LA’s reputation as a land of famous people, most Angelinos never achieve legacy status. Most of us live pretty normal lives and consider ourselves lucky if we have a drink named after us at the local bar or learn our neighbors names. But a select few manage to endure a handful of generations beyond their passing. One such lingering transplant spent most of his time alone and only lived in Southern California for five years, yet his legacy is memorialized with a granite gravestone on a hilltop above Pasadena: Owen Brown, son of John Brown the Liberator.

If you’ve never heard of him, you wouldn’t be the first. I stumbled upon his gravesite on an afternoon hike and had to look him up when I got home. Turns out, Owen was an abolitionist alongside his father, John Brown (the liberator). You may or may not remember John Brown from your US History class, but in case you weren’t paying attention that day here’s what you need to know:

John Brown was one of the most well-known white abolitionists of the 1800s.

He was catapulted to fame for his Raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859.

Harpers Ferry is a town in West Virginia, not an old-timey steamboat belonging to a guy named Harper.

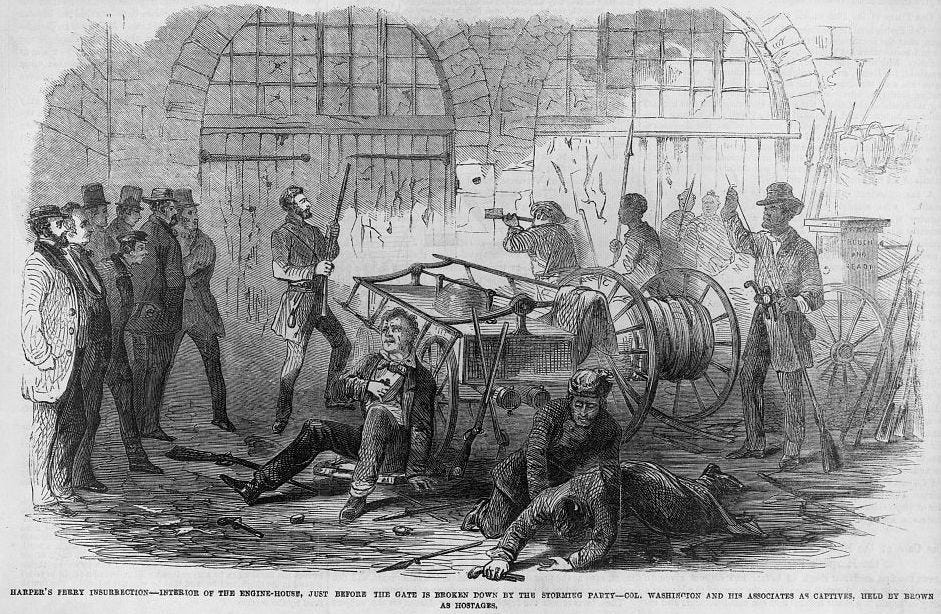

The raid on Harpers Ferry was an attempted seizure of the US arsenal of over 100,000 weapons. It was intended to inspire a slave uprising in the American South.

At the time, the press called it “treason” “rebellion” and “insurrection” — the word “raid” wasn’t used until after the Civil War ended.

The raid was the last major political event before Lincoln’s election, the Southern States secession, and the US Civil War.

Twenty five years before he would arrive in Pasadena, Owen Brown was anxiously guarding supplies at the Kennedy Farmhouse while his father and a small militia invaded the US arsenal and held its workers hostage four miles away in Harpers Ferry.

John and Owen had been living at the property for three months leading up to the raid, importing hundreds of out of state weapons and covertly training a small army of abolitionists. John lived under the pseudonym Isaac Smith, and told curious neighbors he was a gold prospector to explain away the oversize shipments arriving at his front door. He even went so far as collecting mineral samples out in public and taking them back to the farm for analysis to further sell the ruse. A true actor, through and through. Of course his son would end up in LA.

John’s goal was to incite a slave uprising in the South, though his plan was deemed suicidal even by his close friends. Some sources report the untrained and poorly armed militia was disorganized and drunk during the raid. Brown expected over a thousand slaves from nearby plantations to join the raid, but nobody showed. In the end, John Brown and a mere 20 accomplices were quickly overpowered by the army, and everyone involved was either killed in the fight or executed for treason.

Everyone except Owen.

When he caught wind that the raid had taken a turn for the worse, Owen and four others made the split second decision to gather what supplies they could and flee to the mountains. The plan was to head Northwest until they reached some of Owen’s friends in Ohio or, if worse came to worst, continue onward to Canada.

It’s 200 miles from Harper’s Ferry to the Ohio border. Google Maps says it would take 69 hours of continuous walking to make the trek by foot, and that’s taking modern day roads and trails. In 1859, the trek on foot would have been perilous even under the best conditions. Although Owen was an experienced outdoorsman, the odds of making the journey alive were slim at best. He had a $25,000 bounty on his head, nearly $1 million in today’s currency, so traveling by road was out of the question. If Owen was to make it to safety, it was going to be by bushwhacking hundreds of miles through the Appalachian wilderness.

Owen immediately assumed the role of guide and decided the group would travel only at night, sleep under cover during the day, build no fires, buy or steal no provisions, and speak in whispers until they made it North of Pennsylvania. One of Owen’s companions deserted the party only a few nights into the journey, and another never returned after going against Owen’s guidelines and journeying into town for provisions. Owen later learned he had been captured and executed.

The remaining three hiked through the mountains for weeks, living primarily on dry corn, sugar, biscuits, and raw potatoes. They slept huddled together under tarps for warmth and ran from chasing dogs, prowling troops, and suspicious townsfolk. On top of contending with the elements of nature and the bounty on his head, Owen had immense trouble managing his traveling companions. They were younger and wilder — you know, the kind of rambunctious youths who signed up to raid government arsenals. They wanted to take a more gunslinging attitude toward the escape, and on multiple occasions Owen had to restrain them from attempting to steal horses, shoot at squirrels, and light fires to keep warm.

Despite all odds, after a month on the run the trio made it to a network of Quakers in the North who fed them, housed them, and underground-railroaded them to safety. They parted ways and Owen escaped to Ohio where he reunited with his brothers John Jr. and Jason, who were living abroad and hadn’t participated in the raid. Although the imminent threat of capture lay behind him, Owen spent the next decade living under false names and skipping town whenever his resemblance to his father, the now-famous-insurrectionist, raised public suspicions.

Owen lived in relative secrecy for nearly twenty years. He and John Jr. settled in a farmhouse on a dreamy island on Lake Erie, hoping to leave their lives of activism behind them. Even after the Civil War, it was difficult to outrun their father’s legacy. John Brown was the most famous man in the country until Lincoln’s assassination in 1965, and stood as a symbol of the nation’s polarization. Whether you viewed him as a hero or a villain, nearly everyone had something to say about Brown’s legacy.

Eventually, Owen’s past caught up with him and a reporter came knocking. It took journalist Ralph Keeler nearly a dozen informal meetings and interviews, but eventually he managed to wring out the tale of Owen’s daunting escape from Harper’s Ferry. It was the only time Owen ever told the story publicly.

The harrowing account took up 25 pages in the March 1874 edition of the Atlantic Monthly. Mark Twain himself said of the article, “Three different times I tried to read it but was frightened off each time before I could finish. The tale was so vivid and so real that I seemed to be living those adventures myself and sharing their intolerable perils.” To me, it sounds like Twain is saying he never finished reading it, but his review does hold up — the piece is riveting.

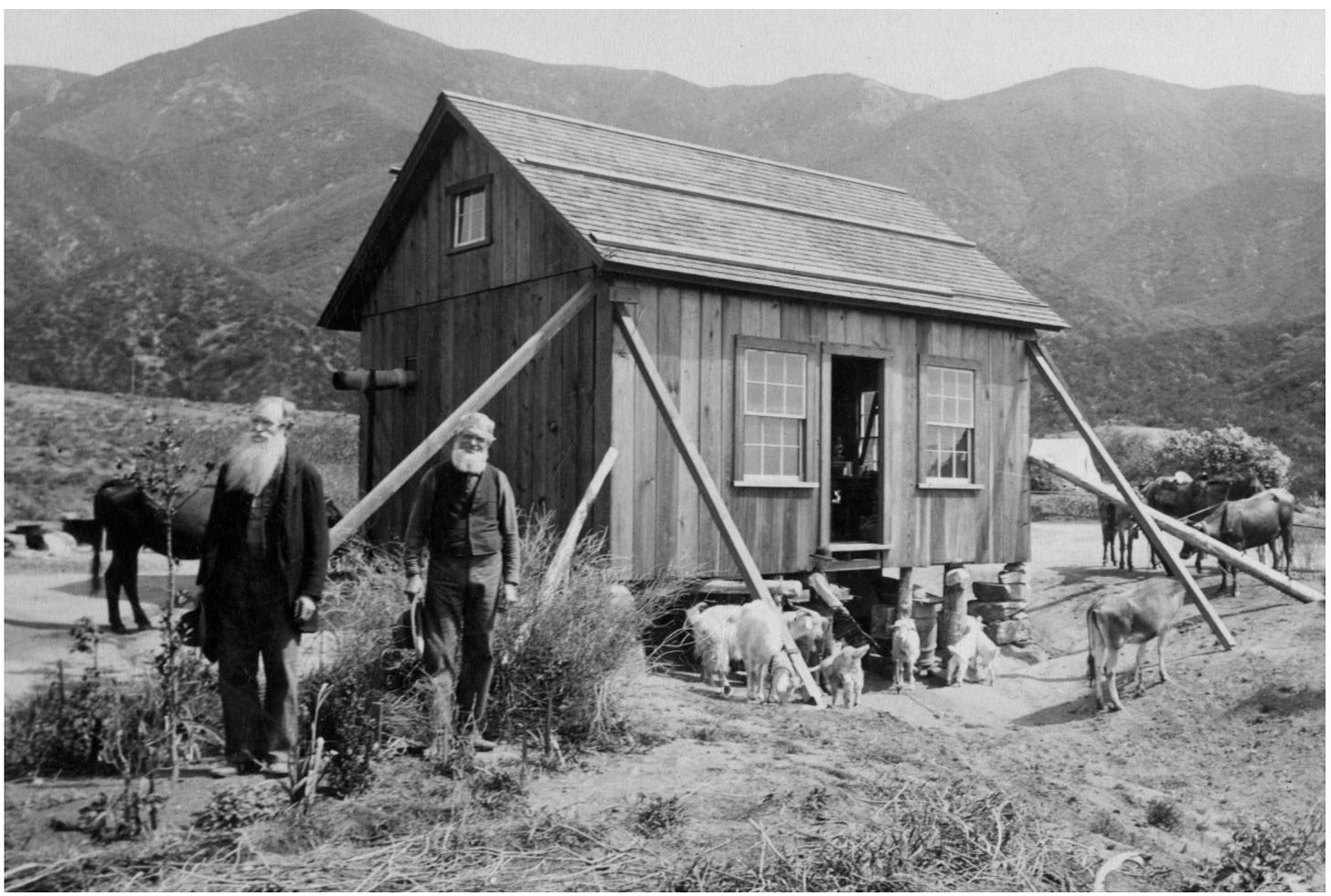

While Owen likely could have become a public figure and made a fortune telling his story to audiences across the country, he didn’t seem eager to speak up about his past heroics, preferring instead a quiet life of solitude. He lived as a recluse for the remainder of his life, spending most of his time fishing, writing, and hanging out with his dog.

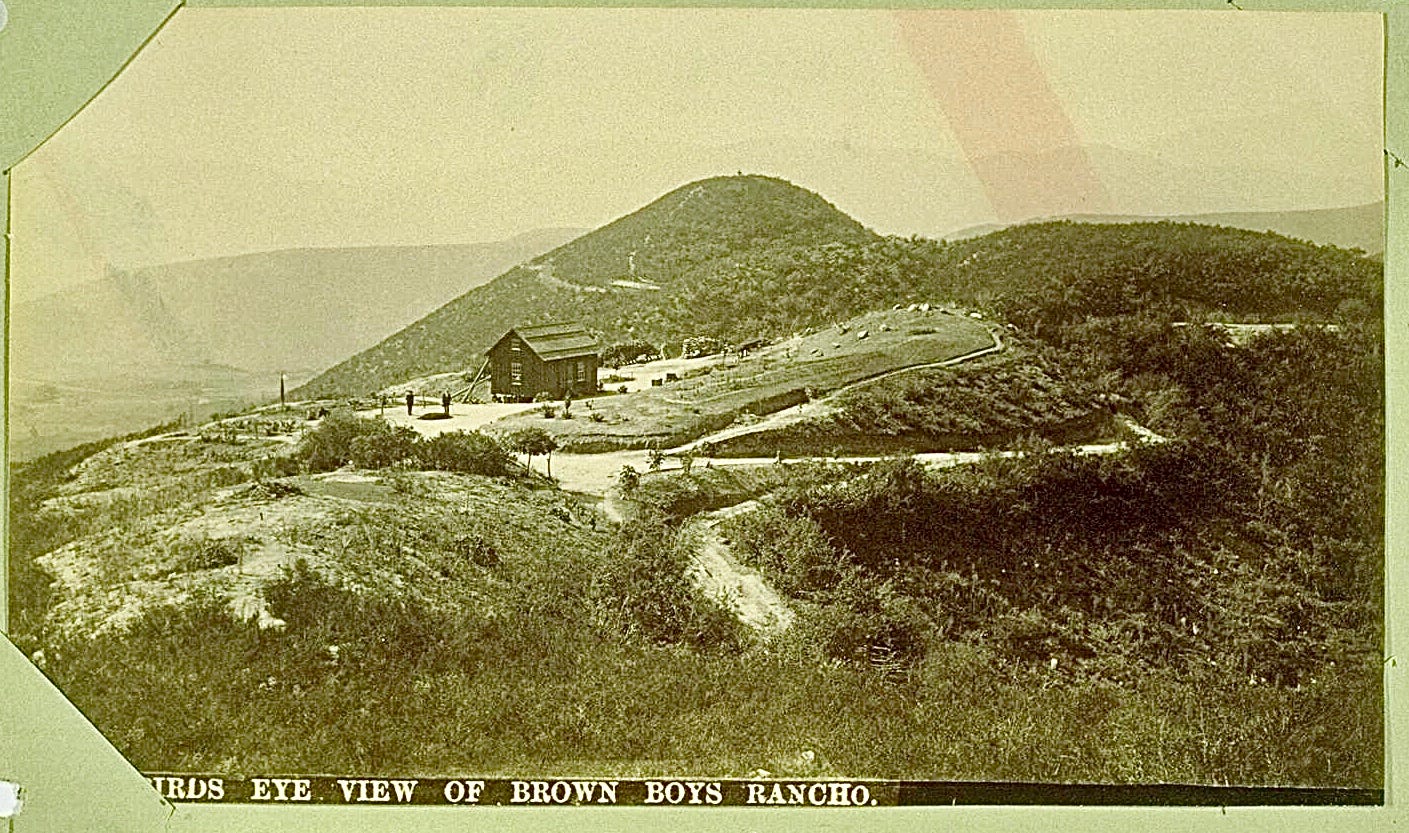

In 1884, Owen’s health was deteriorating and he looked to relocate to a milder climate. He followed his brother Jason out West to a fast-growing town on the edge of the desert: Los Angeles. They built a small cabin together in the foothills of Pasadena.

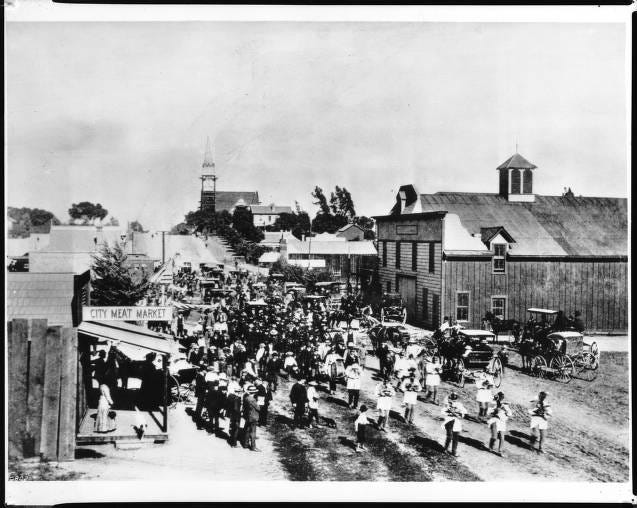

The people of Pasadena embraced the Browns with open arms and applauded their abolitionist achievements. While they would always be associated with Harpers Ferry and their demonstrative youth, in California the Browns oddly became well known for their vocal support of the temperance movement, which was gaining momentum at the time. It just goes to show that no matter your past, in LA you can become whoever you want to be. Yesterday an abolitionist, today an early proponent of prohibition.

For the most part, Owen and Jason kept to themselves in the hills and lived life as homesteaders, farming several acres of land. They were in the process of building a trail to the top of Brown mountain when Owen died of pneumonia on January 9th, 1889. He was buried on Little Roundtop, a small hill near their homestead just off the present day El Prieto Loop trail.

Though the public had granted Owen a degree of anonymity while he lived, he was a bona fide celebrity. Around 2,000 people attended his memorial service — the largest funeral ever held in Pasadena. Nine years later, the granite headstone was installed on his grave, complete with the “liberator” inscription, forever commemorating Owen as an instrumental force in the fight against slavery.

Even in death, however, Owen Brown couldn’t manage to avoid controversy. In 2002, just after the land surrounding the gravesite was sold to new owners, his gravestone mysteriously disappeared from the hilltop. Though nobody was formally accused of dismantling the grave, it’s hard to imagine the disappearance wasn’t intended to make a statement. A decade later, a hiker happened upon the gravestone in a nearby canyon and in 2021, preservationists worked to reinstall the site on top of Little Roundtop and ensure its accessibility into the future.

I wonder how Owen would react if you told him that a hundred years after he died, anyone with an internet connection would be able to read all about his family history, his daunting escape from Harpers Ferry, and his late-life anti-alcohol sentiments. I have to imagine a guy who built a cabin on the outskirts of town wouldn’t be thrilled with how much attention he’s continued to get over the past century. And he’d definitely roll over in his grave to know that I drank a fair share of whiskey while researching and writing about him.

As a transplant to Los Angeles myself, I feel a certain kinship with Owen Brown. I am drawn to these same mountains that he was drawn to, and feel the same sense of peace and calm I imagine he did when I walk along the oak-lined El Prieto canyon.

Standing at his gravesite and looking out over the rolling hills, I feel time collapse. There’s something special about this blip on the map, perched on a hillside between the desert and the Pacific. And if it’s good enough a spot to settle down for Owen Brown, a man who truly embodied the adventurous life, it sure as heck seems good enough for me.

Oh em gee! As an Altadena native *and* anti-racist activist since the 1980s, I HAD NO IDEA! Your intellectual curiosity, elegant writing, and research rigor are magnetic, Casey! Thank you so much for this gift.

Great story. The older I get, the more prophetic seem John Brown’s final words: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Can you give more details on the hike to the grave site?