The Best Lake in the Sierra Nevada

According to one extremely biased source

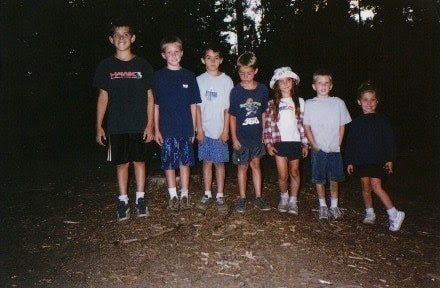

Every summer since I was in elementary school, my family would load up the car with tents, coolers, stoves, lanterns, sunscreen, marshmallows, bug spray, and head out to a secret lake in the Sierra Nevada for five, seven, or fourteen days, depending on how much grief my brother and I had caused my parents during the preceding school year. An assortment of cousins and grandparents, aunts and uncles, and a dopey golden retriever called Cody would meet up there and spend long summer days lounging at the lake, playing kick the can, and telling stories around the campfire.

It was always the highlight of my kid year.

Okay, it’s not really a secret lake. It’s Cherry Lake. Easily findable online, six and a half hours from Los Angeles, just outside the boundary of Yosemite National Park.

I feel comfortable disclosing Cherry Lake to the internet public because there’s honestly nothing special about Cherry Lake. I mean, it’s surrounded by granite slabs and pine forests which are inherently beautiful and therefore kind of special, but there are more than 4,000 lakes in the Sierra Nevada and I’d be surprised if Cherry Lake even made the top 50% of that list in a purely aesthetic vacation destination sort of sense. It’s technically not even a lake, it’s an artificial reservoir that only exists to store water for San Francisco as part of the Hetch Hetchy water project.

In fact, Cherry Lake has some pretty notable downsides. There’s no potable running water (which means no showers or flush toilets either), hardly any sandy beach swimming areas, and the campground isn’t even next to the lake. To swim, you either have to drive a few miles down to the gravel boat launch or brave a treacherous and steep trail down to a small, rocky lagoon and sit perched among the boulders at the waterline.

Cherry Lake is, from an outside point of view, simply an okay lake not too far from civilization. But it’s our okay lake, and a lifetime of memories more than make up for its shortcomings. Multiple lifetimes of memories, actually.

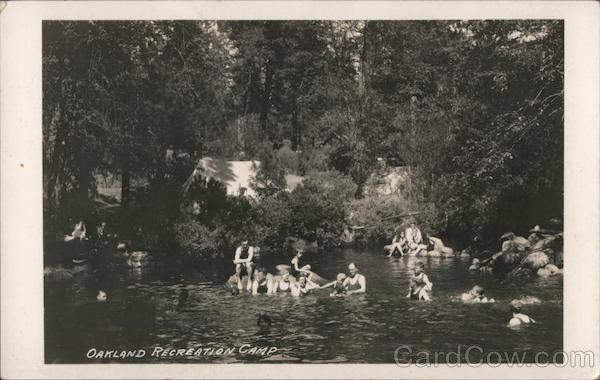

My grandpa first discovered the area when he was 18 years old working at the Oakland Recreation Camp. That year, a forest fire broke out in Cherry Valley and, because 1949 was an absolutely reckless and wild time when there were few if any rules, CalFire drafted barely-legal-age camp workers to fight the fire and my grandpa ended up driving a water supply truck through the mountains when he thought he would be lifeguarding at the pool for summer family camp.

Cherry Lake didn’t even exist at the time. The dam wasn’t constructed until 1956, and the lake was originally called Lake Lloyd. But the area made an impression on my grandpa, nonetheless. So much so that 18 years (and six kids) later, in the summer of 1967, he packed the family station wagon to the gills with children, camping gear for a week, plus a dog and headed for the hills, unknowingly starting a family tradition that would last for decades.

Those early days honestly sound like they were pure survival. My mom and her siblings tell stories of canned corn beef hash and other choice delicacies that kept two adults and six younglings alive for two weeks relying on only a single cooler. There are family legends of bears wandering through camp, lightning storms striking the surface of the lake, and at least one instance of a three mile bushwhack back from the end of the lake when afternoon winds picked up and threatened to swamp their small inflatable raft.

By the time I arrived on the scene in the 90s, things hadn’t improved much. We skipped the canned corn beef hash, but “hobo stew” was an annual staple. Our water bottles were single walled plastic wrapped in a neoprene sleeve, which meant every afternoon I drank lemonade the temperature of hot tea in order to stay hydrated. I remember forgetting what a cold drink tasted like by day three, and actively hallucinating visions of pizza and mcflurries by the end of a ten day stint.

We all slowly refined our practices over the years and, thanks to innovations in camping technology, these days Cherry Lake feels more like a luxury retreat than a survivalist encampment. We enjoy Manhattans on the rocks and cold beer throughout our entire stay. We’ve got food and snacks out the wazoo, and indulge in daily happy hours with cheese boards and fresh bruschetta while lounging in comfortable hammocks and reclining camp chairs. My brother and I work out a meal plan and share our own campsite now, but I’m pretty sure if we showed up with nothing we’d be clothed, fed, and drunk before we knew it.

I find it strange how visiting the same place year after year simultaneously reminds me of how much things change and how much they stay the same. We’ve been staying in the same campsites since I was a child, and they’re largely identical to the way they were in 1997.

In fact, they’re largely identical to the way they were in 1967, according to my grandpa. The towering sugar pine behind campsite 10 has been the backdrop to many a cornhole game for decades now, and the rotting log still sits in the meadow behind campsite 12, continuing to serve as the designated family photo spot.

We remember when they replaced the picnic tables and when they upgraded the food storage lockers. I mean, we don’t actually remember the years, per se, but we can generally get it down to the decade-ish. Everything sort of blends and smears together after a while, and everyone seems to have a slightly different memory of when certain changes took place. But the important thing is that we were there when they happened.

There was the time my grandma thought that ants were termites, and the time my cousin Jonathan capsized the canoe with my kid brother in it. There was the year we forgot the tent poles at home and the year it rained so hard the parents piled all the kids in the van, drove down the mountain, and spent the afternoon walking around Walmart buying tarps and ponchos and asking anyone if they knew when the rain would stop.

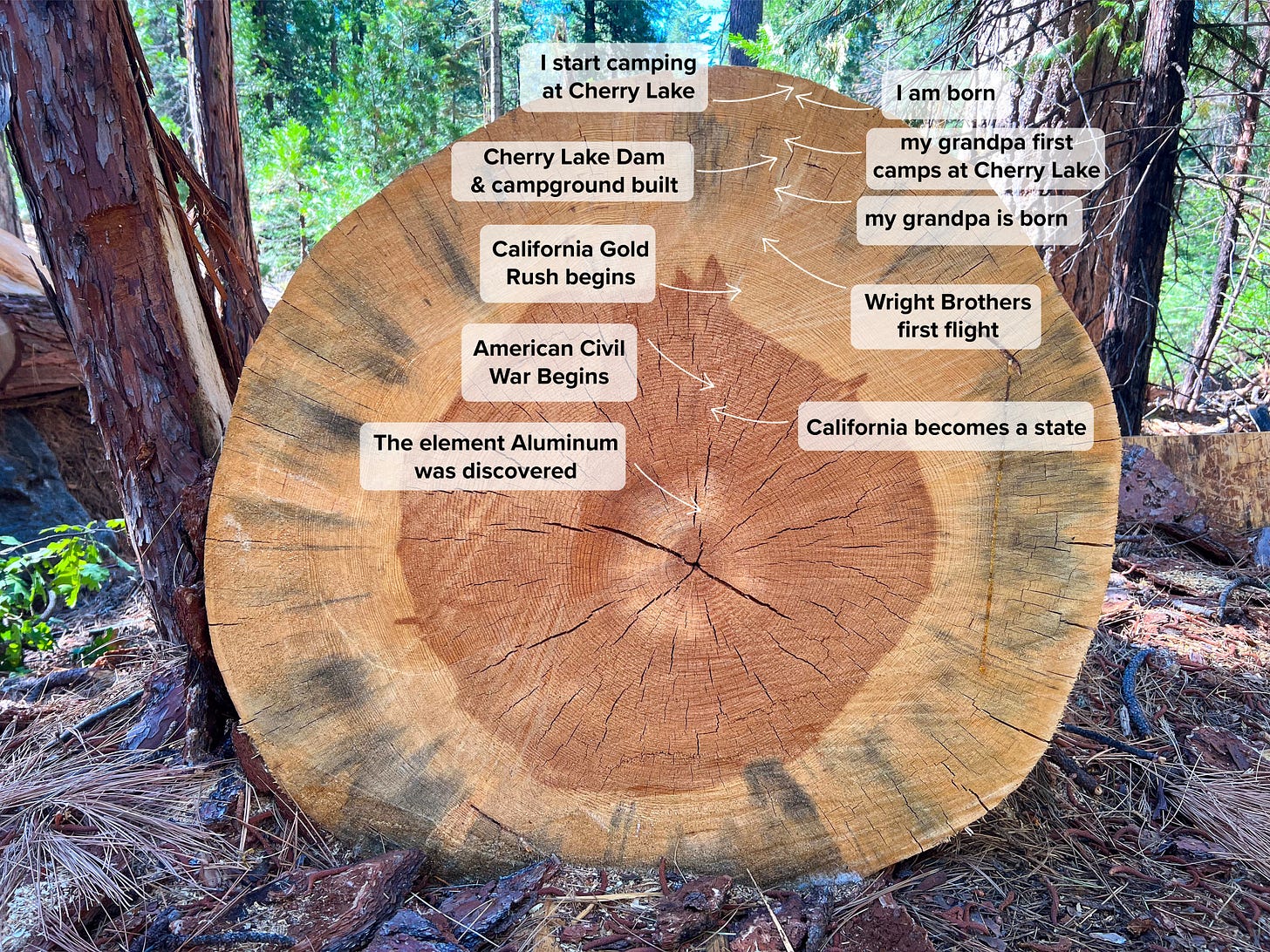

Recently, the forest service chopped down a whole bunch of trees throughout the campground. Perhaps they were dying or diseased or had been damaged in the wild series of winter storms that hit California this winter. Whatever the cause, enormous stumps and fallen logs dotted the campground, adding a new layer of contour to the slowly shifting fingerprint of the forest.

Nicole and I counted the rings on one of them, a massive Ponderosa with a trunk four feet across. It turned out to be somewhere around 200 years old. It was my age when California became a state. It was 100 years old when the Wright brothers made their first flight. It likely lived a century in the forest with the deer and squirrels before seeing a single human being.

Our group has evolved over the years from a feral band of pre-teen cousins fighting for survival in the bush to a relatively mature group of adults getting away from it all for some time in the woods. The crowd has ebbed and flowed over time depending on work schedules and availability, but some core group of us makes it up every summer. Four years ago I started bringing my wife Nicole up to the lake, and sharing it with her has added an entirely new layer of meaning to an already special place.

My grandpa is 92 now and hasn’t camped at Cherry Lake in a number of years, but this year he managed to make it up for a single afternoon. He boated around the lake, lounged in the campground, and seemed to have a great time getting back to the place he stumbled upon so many years ago.

This year, my cousin Collin brought Dean his one year old son up to Cherry for the first time, making it the first time that four generations of my family were at the lake in the same year. Four generations is wild to me, and even wilder that it all happened in only the outer few inches of a 200-year-old tree stump.

It has me thinking about how, so often, the only thing that makes our favorite places our favorite places is that someone came before us and decided to stake out their tent and stay a while. Favorite places are ordinary places plus the passage of time. We infuse places with meaning by sharing meals in them, laughing in them, sleeping in them, and reflecting in them.

We all remember how Cherry Lake has changed over the years. But more so, Cherry Lake serves as a guidepost to help us recognize how much we have changed. Cherry seems to exist in a magical eternal present. A liminal space in the mountains we return to year after year, decade after decade, where we can step right back into unfolding time as if we’d never left.

Thanks for sharing this -- what a great example of finding the magic and beauty of a place without having to chase it down on a "most beautiful spots in X" checklist :)