Samuelson's Bizarre Rocks

Who is responsible for the enigmatic carvings in these Joshua Tree boulders?

The desert landscape has forever attracted a curious cast of characters. The vibrant painted domes of Salvation Mountain. The solitary desert fathers of mystical religion. The dazzling Burning Man festival, and the alternative Slab City community. The desert is home to infinitely unique brands of weird.

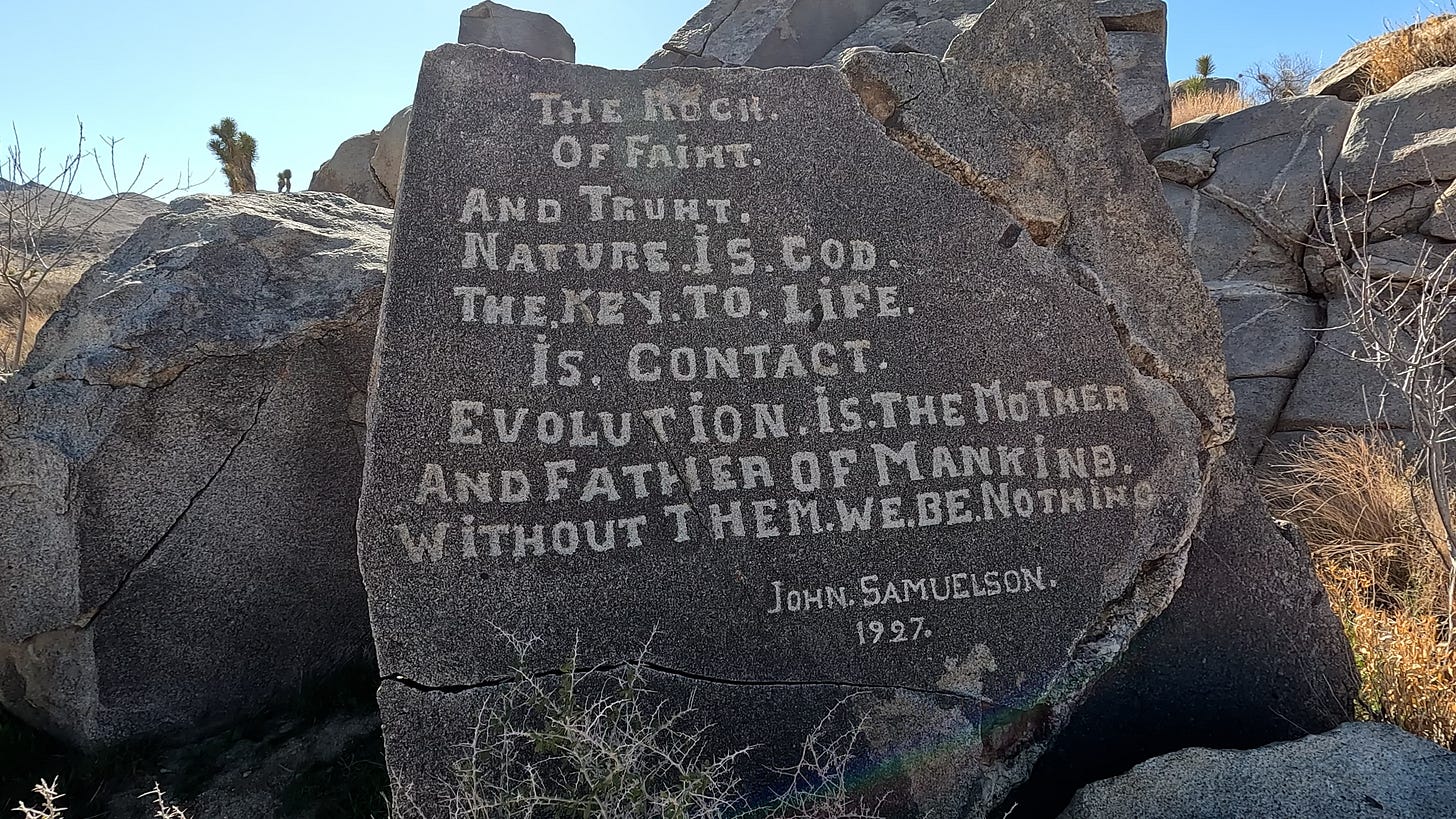

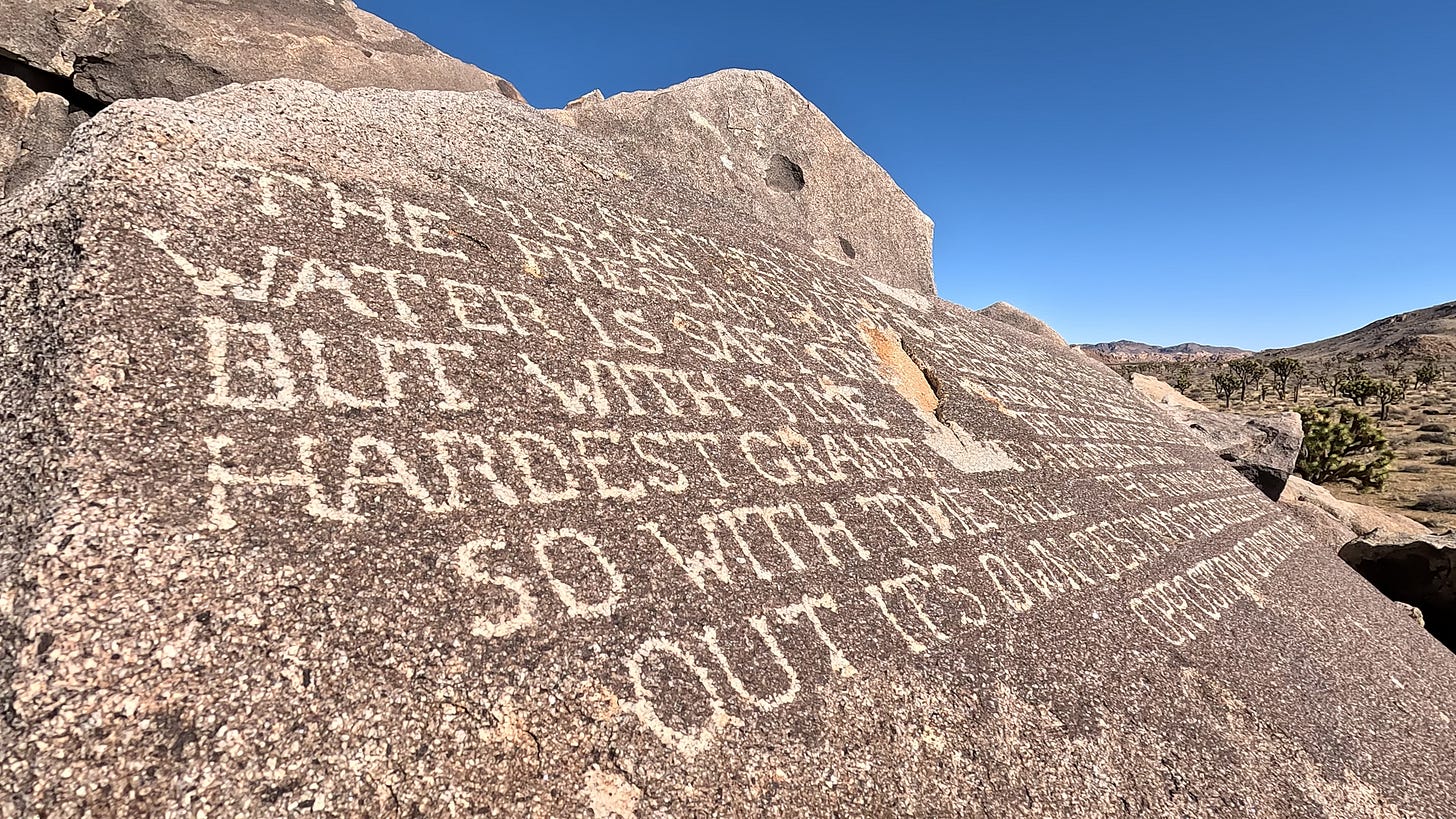

One such peculiarity is located just within the Northern bounds of Joshua Tree National Park. After parking at a nondescript turnout and following a faint trail for a mile into the desert, then wandering up an unmarked wash, passing the shell of an old truck and the remnants of a small cabin, you’ll arrive at an outcrop of boulders. A prominent stone a dozen feet tall stands guard at the northern edge of the pile, its smooth face etched with all-caps scrawl:

You’ve arrived at Samuelson’s Rocks, a collection of nine cryptic inscriptions carved into seven stones in the Mojave, a mile and a half from the nearest road.

The etchings look as if they were chiseled yesterday. The arid conditions preserve Samuelson’s voice in a way no other environment could. From decade to decade, time operates on a different scale in the desert, far removed from the pulsing inputs and outputs that transform forests, bogs, and coastlines. Perhaps this timeless quality is what draws the hermits, artists, and mystics to seek refuge there, far from the influences of mainstream culture.

Once you’ve convinced yourself that you are in fact looking at hundred-year-old carvings and not the work of a modern-day Banksy, you can’t help but wonder what was going through the mind of the carving’s author. John Samuelson ended up in the California desert via a long, meandering path. Many years before, he claims he was shipwrecked on a mysterious island off the coast of the African continent where he came upon a mystical tribe of natives. He lived many adventures on the island, including discovering a gold treasure guarded by man-eating ants and seducing the tribal chief’s daughter, before a medicine man forced Samuelson to eat the “bread of forgetfulness” and extricated him to the nearest colonial outpost, where he woke up with no memory of who he was or what had happened.

The only reason we know any of this is because in 1928, Samuelson had a few too many drinks with pulp fiction author Erle Stanley Gardner and divulged the entire tale, which had apparently come back to Samuelson over the years in fragmented dreams. Gardner bought the rights to the story on the spot for $20 “At the time,” Gardner says in the tale’s introduction, “I thought it was just a wild lie of an old desert rat. [Eventually] I came to believe it was true.”

After the shipwreck, Samuelson made his way to Boston where a doctor of tropical medicine studied him for six months in an effort to cure his lapsing memory. The “bread of forgetting” had not only caused Samuelson to lose his memory of the entire shipwreck escapade, it left him suffering amnesiac blackouts whenever it rained. Unable to find any lasting remedy, the doctor finally suggested that Samuelson simply move out West where the weather was better. In the early 20s, John Samuelson landed in what would eventually become Joshua Tree National Park, where it only rains a handful of times a year.

Who knows how much of the account Gardner actually believed, but it made for one hell of a narrative. It is difficult to pick apart the truth and fiction of Samuelson’s past. Like most folks who settle in the desert, Samuelson was a pretty solitary guy.

He spent the late 1920s preserving his musings in stone, eager to share his truth with anyone who would listen. His etchings land somewhere between eccentric conspiracy theorist, new age philosopher, and grumpy anti-capitalist. They allude to political figures of the day with such specificity that a modern day spectator can’t help but wonder just what it was that Samuelson was trying to say. Before the age of email, twitter, and instagram, this was one man’s attempt to make his voice heard. A shout into the void.

Samuelson’s legacy took a tragic turn in 1942 when he shot and killed two people during a bar fight in a neighborhood south of Los Angeles. He was jailed without bail, and pleaded not guilty to murder by reason of insanity in order to avoid the death penalty. The court committed him to Mendocino State Hospital on April 8, 1943, where he was sentenced to live the remainder of his days.

Several years later, while working on one of his more well-known pulp series, Erle Stanley Gardner found himself back in the Mojave and went searching to see what had become of Samuelson’s old homestead. He found the old cabin completely leveled, with only the cryptic stone carvings left as evidence that Samuelson had ever inhabited the area.

While wandering through the boulders, however, Gardner happened upon a new carving he had never seen before. Perhaps he had just missed it many years before, but he had a strong hunch that he had not, and that it had in fact been added more recently. He wrote a letter to Mendocino State Hospital inquiring after Samuelson, and received a haunting reply:

“On July 1, 1946, the patient ran away from the hospital, and no word has been heard from him or about him by anyone up to this time. He did not go home, and he did not contact his wife; and nothing is known as to his whereabouts.”

We’ll never get to know exactly what Samuelson was trying to say with his desert proclamations. Maybe he was a poet ahead of his time, or perhaps his rocks are nothing more than a portrait of a man losing his mind in solitude. Or maybe, everything he told Gardner was the truth, and, in Gardner’s words, “somewhere in the shifting sands of the California desert is an old prospector, hiding from the rain, digging for gold, cherishing lost memories.”

Next time you find yourself in Joshua Tree, make the trek and see Samuelson’s rocks for yourself. Maybe you’ll uncover some hidden meaning in his enigmatic phrases, or perhaps you’ll be the lucky soul to uncover his tenth dictum, hidden in the desert stone for the last hundred years.