A Brief History of Los Angeles Floods

"City in a grasp of swirling water. Wheels of traffic generally halted and the populace marooned." - LA Times, February 19, 1914

We make a big to-do about rain here in Southern California. Breaking out the rain boots at the first sign of drizzle is part of our identity, and it really is fair to say that most SoCal drivers don’t know how to handle a downpour.

But can you blame us? It rains only 36 days per year in Los Angeles, and 90% of that rain is concentrated in a few short months. Pair that with steep, sandy mountains to the north and east that funnel water to the ocean and you’ve got a recipe for some significant weather events—though they may remain few and far between.

One such storm made the front page of the February 19th, 1914 Los Angeles Times.

“Between 12 o’clock noon and 2 o’clock, two inches of rain came upon the city in a deluge which knows no parallel here.”

“There were no fatalities or serious injuries, and the only real inconvenience was the marooning of the populace downtown and flooded homes in the lowlands. Downtown Los Angeles was inundated and residence, industrial, and commercial districts were flooded by the rain, but only for several hours yesterday.”

For a city that likes to play up its weather events, I actually think the editors showed restraint on this one. The flood control district of LA, however, was not so cavalier.

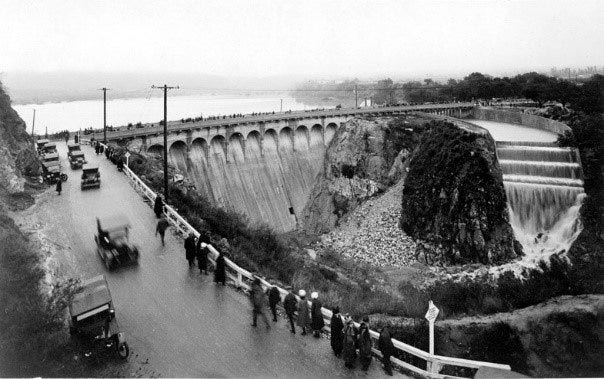

They determined that a marooned downtown and flooded lowland homes required action and introduced their first line of defense in what would become a century-long war against flooding in Los Angeles: Devil’s Gate Dam.

Located on the border of Pasadena and La Canada Flintridge, the dam was constructed in 1921 and continues to be an integral piece of LA flood prevention to this day.

It’s most famous for being haunted (allegedly) and though I’ve yet to see a ghost there, the devilish rock face for which it is named is unsettling. Dozens of canyons upstream catch rainwater in the San Gabriels and coalesce into the Arroyo Seco below, which flows through Devil’s Gate and is one of the primary tributaries of the Los Angeles River.

During a downpour, these canyons spit out a lot of water:

Twenty four years after the historic flood, an even larger storm system put LA’s flood prevention infrastructure to the test.

In March of 1938, a storm generated almost a year’s worth of precipitation in just a few days, killed 115 people, destroyed 6000 homes, and left one third of Los Angeles underwater; an almost unfathomable idea in drought-parched Southern California today.

The storm was so powerful it relocated the banks of the LA River up to a mile in some places. At the time, the Red Cross deemed it the fifth largest flood in history.

Devil’s Gate Dam, while structurally intact, was not enough to ward off the floodwaters.

This prompted the City of Los Angeles to reconsider how it dealt with excess storm runoff. They didn’t appreciate the fundamental ever-changing nature of rivers, as it generally messed with their city-planning.

The solution they found was simple, robust, and monumentally shortsighted: cement the whole thing, and freeze the river in place.

We don’t have time to get into it here, but suffice it to say this has been hugely problematic for the greater river ecosystem in Los Angeles, not to mention the fact that during storm events it jettisons millions of gallons of desperately needed fresh rainwater directly into the ocean with almost zero recapture system to speak of.

But it did accomplish one goal: mitigate flooding. We haven’t had a significant flooding event in Los Angeles since.

But all solutions eventually create their own problems, and Devil’s Gate Dam is no exception.

In 2009, the Station Fire burned 160,000 acres of the San Gabriels—the most severe fire in LA History. But the fire turned out to be only half the problem. That winter, with no vegetation left to hold the sandy mountain sides together, storms carried more than 1.3 million cubic yards of sediment into Devil's Gate Reservoir.

Enough to fill the Rose Bowl three times.

As in the case with literally every dam ever constructed, sediment build up is 1) inevitable and 2) a huge problem. Not only does it present a structural threat to the dam itself, it also severely reduces the reservoir's capacity.

Until recently, the Devil’s Gate Reservoir lacked the storage capacity for even one major debris storm event. A repeat of 1938 appeared almost inevitable—this time with exponentially more people living in the basin.

Fortunately for everyone living downstream, in 2019 LA Public Works began an excavation project to remove 1.7 million cubic yards of sediment from the dam area, increasing the reservoir’s capacity. 10 years in the planning, the Devil’s Gate project has encountered a wide variety of criticism ranging from diesel particle emissions near schools to the environmental impact reports overlooking nearly 500 native Southern Steelhead, an endangered species thought extinct in the Arroyo until recently.

The video is 18 minutes long, but a super fascinating look at native species in Los Angeles.

But flood control is the winning priority so far and over the course of the last 4 years an army of dump trucks have removed thousands of loads of sediment from behind the dam, distributing it at two plants in Sun Valley and Irwindale.

I don’t know what Irwindale did to deserve a giant pile of dirt dumped on their front door, but so it goes.

As impressive as the operation is, and as grateful as I am that the city won’t be swept away in a major debris storm event next winter, the excavation project feels like a tiny bandaid on a gaping wound.

Devil’s Gate Dam was originally constructed in only 13 months. The project to remove sediment buildup from a single wildfire took 10 years of planning, 4 years of active excavation, and will require ongoing annual excavation around the base of the dam in perpetuity.

I’m no civil engineer, but it doesn’t feel like an elegant solution.

But for now, at least, it’s working. In January 2022, after the much-welcomed December and January rains, I finally watched the reservoir fill with water for the first time since I’ve lived here. The excavation project went as planned and the lake actually looked nice while it lasted, reflecting the oaks below the towering mountains. Of course I didn’t manage to take a picture of it, but here’s one from LAPW.

It’s true that we still can’t drive on the freeways in the rain without crashing into one another, but we’ve at least managed to curtail the next downtown-marooning flood for the time being.

Only time will tell when the next big storm decides to test our aging infrastructure again.